Saxon London By David Nash Ford

When Anglo-Saxon settlers first moved into Britain in the 450s, they quickly began to divide Britain up into numerous petty kingdoms. Though London fell within the Kingdom of the East Saxons, its importance was obviously recognised by these newcomers and the city was often taken under direct control of the Essex overlords: variously Kings of Kent, Mercia or Wessex. The area within the old Roman walls was left almost wholly deserted, though there may have been an Essex Royal Palace somewhere nearby. Soon after the arrival of Christianity in the Saxon parts of Britain in 597, however, King Aethelbert of Kent built the first St. Paul's Cathedral within the Ludgate, supposedly replacing a pagan Saxon temple. St. Augustine had been sent, by Pope Gregory I, to establish two archiepiscopal sees in the metropolitan centres of London and York. He instead settled for the more accommodating people of Canterbury and Kent as his flock and, in 604, St. Mellitus was established at St. Paul's under the patronage of Aethelbert and his subordinate, King Saebert of Essex. Both Kings died twelve years later, Essex & London returned to paganism and Mellitus was forced to flee the city.

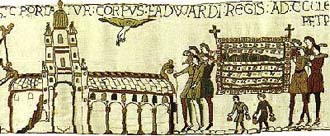

By the 640s, a trading settlement began to establish itself west of the city walls in what is now the Strand and Charing Cross. This naturally advantageous position had the added political benefits of being on the boundary of a number of kingdoms. Lundenwic, as the area had become known by the 670s, grew into a thriving emporium: 'a market for many peoples coming by land and sea' as Bede described it. Saxon timberwork has been discovered reinforcing the Strand Embankment, while wooden homes stood to the north. Archaeological finds of pottery and millstones from France and Germany show London's expanding international trade, and it is probable that foreign ships passed easily through the, by now, ruinous London Bridge. The first coins minted in Britain since the Romans were produced there and stamped with the word Lonuniu. In 675, St. Eorcenwald became Bishop of London and solidly re-established Christianity in the city after the rule of several inefficient prelates. Around the same time, the Mercian Kings from Midland Britain became dominant over the city and may have established the first monastery at Westminster. They held councils in Chelsea and appear to have built a Royal Palace in the ruins of the old Roman fort and amphitheatre. St. Alban's Church, Wood Street is said to have been the 8th century Chapel Royal of King Offa (of Offa's Dyke fame) and may have earlier roots. Elsewhere in the still deserted city, new paths began to emerge through the dilapidated Roman buildings.  Attacks from Viking Raiders started in earnest around Britain in the 830s and it wasn't long before they moved on London. There were attacks in 842 & 851. Then in 865, the 'Great Heathen Army' invaded East Anglia and began to march across the country, raping and pillaging as it went. The Vikings spent the winter of 871-2 in London, presumably within the walls. It is unclear what happened to the traders to the west at this time. By 878 though, King Alfred the Great had become King of all the English and forced the Viking leaders to sue for peace. Eight years later, he re-established Lundenburg, within the city walls, as one of a system of defensive burghs around the country. A South-Werk was also constructed across the river to protect the ferry crossing. With the Roman walls repaired and the ditch recut, Alfred handed the city over to Ealdorman Aethelred of Mercia. The latter established Aethelred's Hythe (Queenhythe) and Billingsgate Market and a new street system began to emerge. Trade prospered and Lvndonia coins were minted in the city, but development was slow at first. Lundenwic was abandoned, though the name survives today as the Auld-Wych. Upon Aethelred's death in 911, London came under the direct control of the English Kings. Through the 920s, the city became the most important commercial centre in England with eight moneyers within its streets. Contemporary writers speak of exotic international trade. There were markets at West (Cheapside) & East Cheap and much industry has been excavated in the form of decorative metalwork and weavers' loomweights. London became a political focus too. King Aethelstan held many Royal Councils in London and issued laws from the city, but the place also had its own government. The city was divided into twenty wards with an ealdormen in charge of each. He was a commander in war and a judge in peace-time. London also had its own Portreeve, a precursor of the county sheriff, who was responsible for collecting taxes. The Peace-Guild was established to pursue criminals. Another body, the ancient popular assembly, known as the Folkmoot, traditionally met at St. Paul's Cross in the Cathedral churchyard, but may have originally taken over the Mercian Royal Palace at the old Roman amphitheatre. Guildhall was later built on this site. The busy city was full of small wooden houses. Stone was reserved for churches. All Hallows by the Tower still retains a Saxon arch. Other fragments survive at St. Brides, Fleet Street & St. Nicholas Shambles. King Aethelred the Unready favoured London as his capital and issued the Laws of London there in 978. It was during his reign that Viking raids returned and were soon transformed into a purposeful campaign to overrun Britain. The Londoners resisted the forces of King Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark in 994 and numerous attacks followed. By 1013, the Dane was besieging the English King in London itself, and Aethelred was forced to flee abroad. Sweyn died the following year, but his son, Canute, continued to lead the Viking armies and overran the city. However, an old Norse Saga tells of Aethelred's return at the Battle of London Bridge (its first mention in Saxon times). The king and his ally, St. Olaf of Norway, managed to manoeuvre their ships beneath this river crossing and "tied ropes around the supporting posts, and rowed downstream as hard as they could....until....the bridge fell" along with most of the Danish garrison. Hence perhaps the old rhyme, "London Bridge is falling down". King Aethelred died two years later and was buried in St. Paul's Cathedral. His son, Edmund Ironside, continued to try to hold back the invaders. He defended London so well, particularly the rebuilt bridge, that Canute's men were forced to cut a large channel to the south in order to get their ships close enough to the city to land. Archaeologists have recently discovered possible indications of the truth of this unlikely story. Edmund escaped from London, but later defeats forced him to share the country with Canute. Within months though, Edmund was dead and the Dane established himself as sole King of England. The Danes had a large community outside the city walls based around the church of St. Clement Danes. Canute's son, King Harold Harefoot, was eventually buried there after his body was exhumed from Westminster and thrown into the Thames. The perpetrator of this macabre event, his brother, King Hardicanute, himself died at a Wedding Feast in Lambeth. In 1042, Canute's step-son, King Edward the Confessor of the old Saxon line, was invited to take up the throne of England. He restricted Royal Councils to meeting at only a few major centres: Gloucester, Winchester and, of course, London. Edward was a very pious man and is best known for re-founding the great Abbey at Westminster, along with the adjoining palace. This second nucleus and Royal rival to the city was to cause political & economic tensions in future centuries. Construction work was completed in 1066, only weeks before Edward's death. He was buried in his new foundation. Edward had no clear heir, and his cousin, Duke William of Normandy, claimed that he had been promised the English throne, a position supposedly confirmed by the citizens of London. The Royal Council, however, met in the city and elected the dead King's brother-in-law, Harold as King. He was crowned in Westminster Abbey and William invaded England soon afterward. London sent a large force of men to the ensuing Battle of Hastings to fight for Harold, under Ansgar the Staller, the Royal Standard Bearer. They were not victorious.  |